Nathan J. Brown

It’s not What People

Believe; It’s What

They Do

Issue #02 — Transforming Environments

Managing Old Problems in a New World

Today, a third of a century after the phrase “new world order” was commonly and optimistically used, each of its elements may seem to be mocking the current period of conflict and polarization. The “order” anticipated in the late twentieth century was to be liberal, peaceful and democratic. But trends now seem to be moving in the opposite direction—towards illiberalism, violent conflict and authoritarianism. Optimistic references to the “world” were based on what all members of humanity share, but politics now seems to be based on disagreement. And rather than a new agenda emerging, the subjects of current disagreement seem to be old—identity, religion, justice.

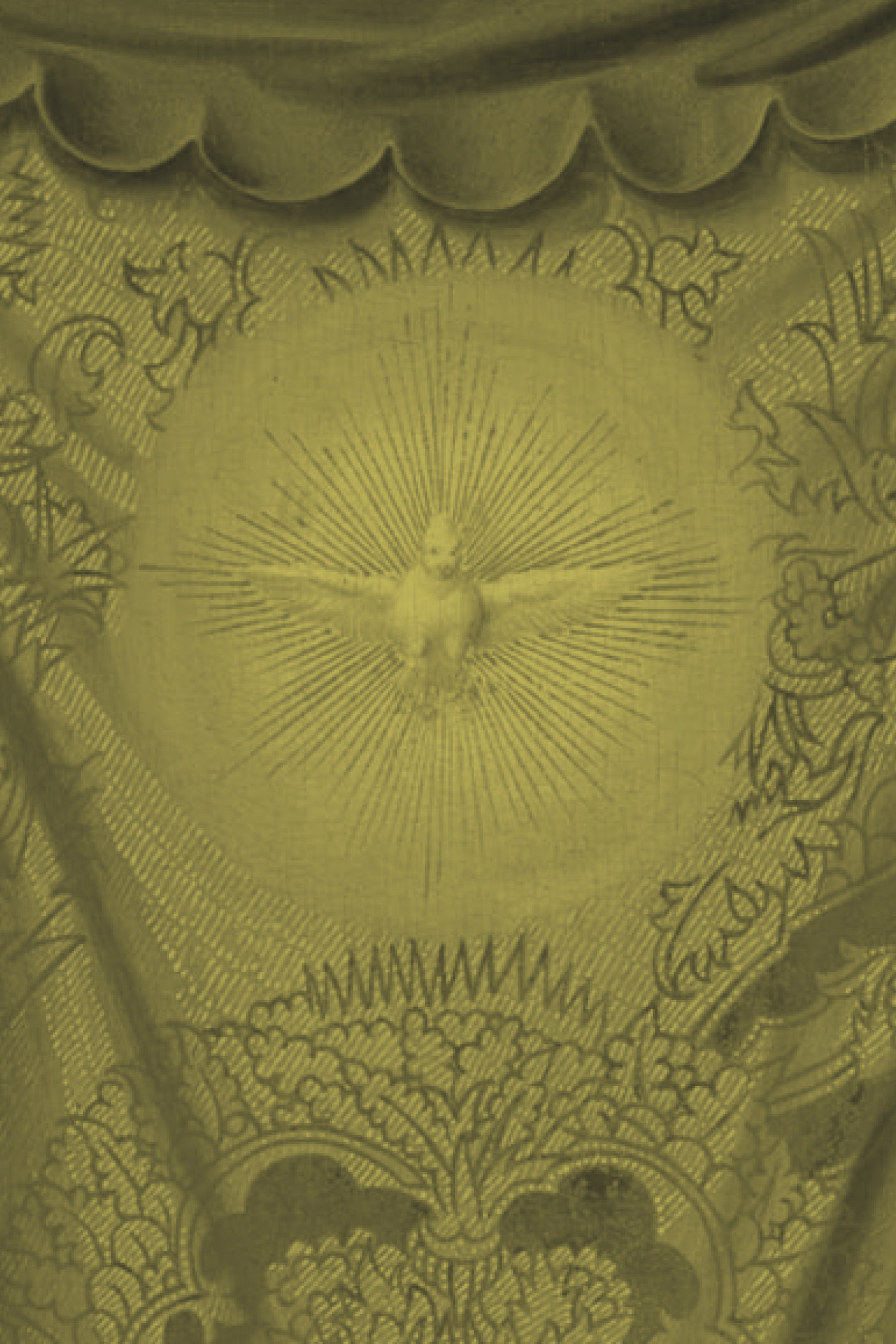

Religion seems at the heart of much disagreement. How can those who begin from one set of religious truths agree with those who begin from another? argue from a religious foundation accept the claims of those who do not—and vice versa? Secularism is one response to such disagreements—it insists that beliefs are private and should not guide politics. For many living in a secular world, bringing religion into political or other spheres makes conflicts unbridgeable. But secularism’s incomplete triumph may only change deep conflicts rather than resolve them. For many of the faithful, losing religious guidance in public life is the problem.

But such pessimism linking religion with conflict, polarization and disorder may itself be the problem. It only deepens conflicts by making them seem essential. Religion and religiosity—or their absence—may indeed lead to deep differences but differences do not necessarily engender conflicts. It is thus without irony that I refer here to a religious tradition other than my own when I quote the Qur’an: “We have created you out of a male and a female and made you into peoples and tribes so that you might come to know one another.”

Is such a hope naïve? I think instead it is based on a realistic view of politics. Were humans to have no differences, politics would be unnecessary. And much learning and growth would disappear in a stagnant sea of homogeneity. So we should move beyond a view of politics as based on what we share and instead focus on how we disagree. I wish to suggest that our divisions may be more manageable than may initially seem. And that can happen if we acknowledge that for all their depth, what is really challenging about our differences about religion is actually their form and immediacy.

The global focus of the “new world order” was not misplaced but it may have overstated how easy it is to live together in a world where we are brought close together and become more aware of our disagreements. Migration, both forced and voluntary, has brought deep differences into matters of daily life; social media have created transparent communities in which self-referential groups carry out discussions among themselves in echo chambers—but ones in which non-members easily overhear what is being said. It is difficult not to hear the most outrageous and intolerant statements that are shouted out from camps other than our own. And that physical and virtual proximity is what makes it so often seem that we live not under conditions of a “new world order” but a disorderly old world.

A basic sense of shared humanity seems more in evidence now than in past eras. It is their immediacy that makes them challenging today.

But what makes the disagreements so difficult today is not that their depth is new; if anything the precise opposite seems to be the case. A basic sense of shared humanity seems more in evidence now than in past eras. It is their immediacy that makes them challenging today. The “world” in which we hope some “order” might emerge is one in which people cannot avoid each other.

So many of the difficult conflicts that we see in daily life come not because we value things differently but because we do things differently; our own established ways seem natural and those who do things differently thus can appear to be acting according to different natures. When we encounter people who do things very differently, we can rush too quickl to assume it is because their values are fundamentally different—but very often it is how they understand how those values are to be applied in a particular case.

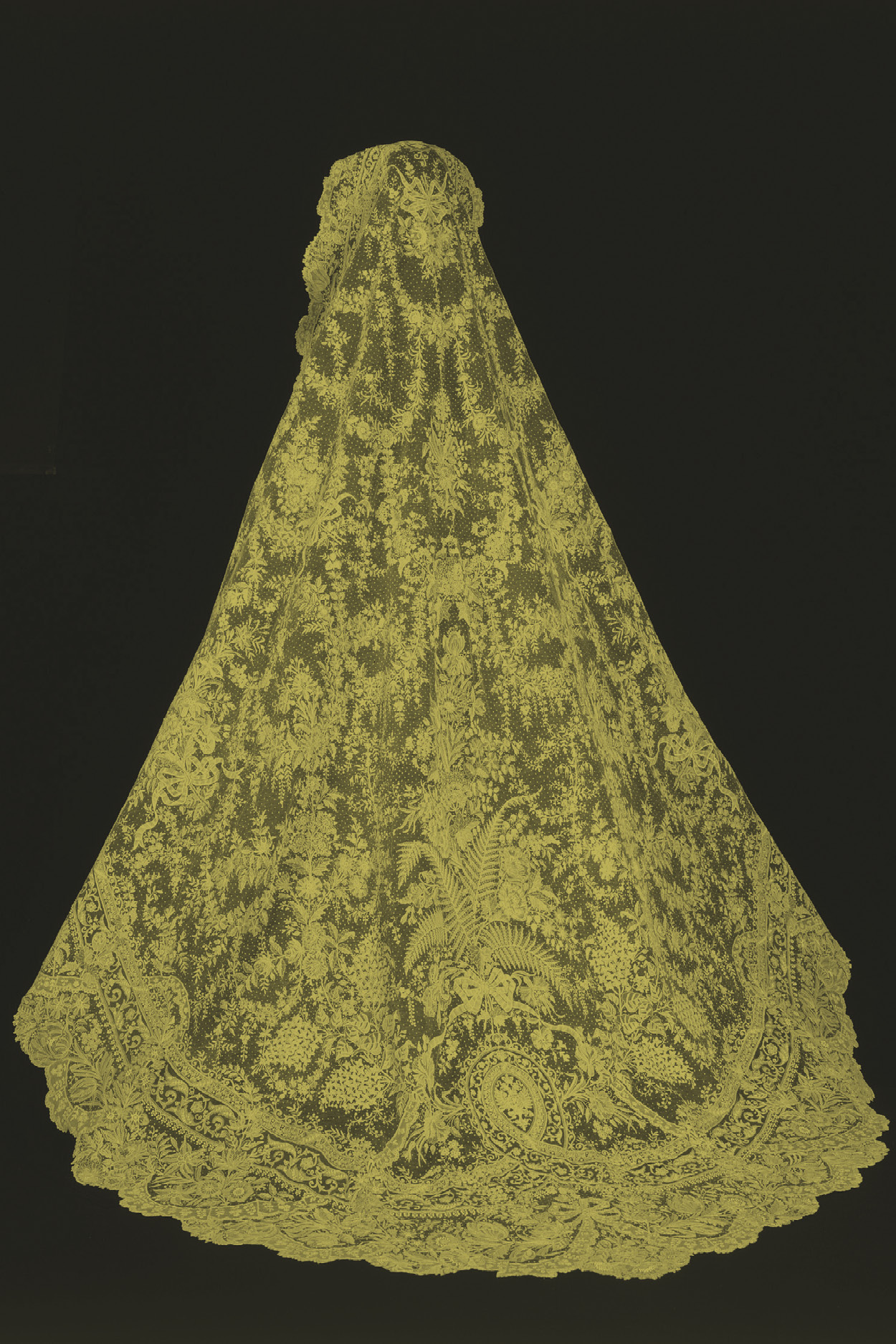

Casebooks of constitutional law can be written about the politics and laws regulating women’s head coverings. There seems to be no issue on which each society frames the fundamental questions so differently, but sometimes arguing from the precise same principle: tolerance, religious freedom, state fairness, individual rights, communal rights. There are differences in how people balance private freedom and public morality to be sure. But those who oppose female subjugation can decry “imposing” the veil; others use the same principle to oppose making female bodies the subject of state regulation. So there is much more general common ground on matters of principle than people are often aware of. The most profound differences concern the detailed application of those principles.

So when I enter a classroom and start a discussion about the subject, I am almost always struck by how the policy issues seem easy and obvious to each individual (depending on a participant’s background) and often stress the same underlying values: freedom, fairness and human dignity. The policy differences are real but they become particularly conflictual when people see their own preferences as so obvious and natural that they assume those who disagree do so because they do not see things clearly. Policy paths followed can change particularly radically as one crosses state borders.

I selected the example of head coverings for a reason: they are a political issue in many societies but also a very personal matter for those who wear them (or not). And many of the polarizing differences within and across societies equally link the intensely personal with the political. A large number involve family life. Who gets custody of children? Who should teach children and what should they be taught. Who can get married—and whose approval is necessary? Again, differences in principle are often less profound than they seem and differences in practice far greater. In my work at the Hamburg Institute for Advanced Study, I have been focusing precisely on such arrangements and how they differ globally.

To return to my earlier claim, that is the task of politics: not to impose uniformity but to find ways to manage difference.

And what I find is that abstract ideas cross international borders with greater than expected ease: the best interests of the child; the role of law in protecting the weaker party; the interests of entire societies in stable and healthy family life; deference to the decisions of parents to raise children in the manner that seems appropriate to them; the freedom of groups who share religious traditions to observe them and transmit them to the next generation. Yes, there are differences in how these are understood and how much they are stressed.

But the real conflicts arise when people cross borders or talk across them—when they have very different ways of doing things and very different reactions to arrangements for schooling, communal worship, custody, marriage and divorce.

And those conflicts fill the files of consular officers are filled with custody disputes; of school principals with complaints from parents about instructional material; with municipal officials with disputes about construction of new houses of worship; with editors of newspapers and administrators of websites with expressions that are taken by some to be disrespectful or impious.

And it is thus in matters of practice and practical arrangements that universalism fails us: there is no easy way of accommodating those who have such different expectations of what is the natural way to do things. The task for those who wish for a new world order is not to eliminate difference over fundamental values but to manage a world where people who pursue those values do so in such different ways—and come into direct contact while doing so. More abstractly, the challenge of the current moment is how to manage a world where widespread values seem to conflict in practice with each other.

To return to my earlier claim, that is the task of politics: not to impose uniformity but to find ways to manage difference; to make the different ways people understand the same principles understandable rather than offensive or threatening. That is more difficult in a world in which people do things so differently.

Nathan J. Brown

is Professor of Political Science and International Affairs and Nonresident Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC. His fellowship at HIAS was devoted to drafting a book manuscript tentatively entitled Religion in State, an effort to ask broadly why states structure religious institutions the way that they have and how official structuring of religion changes over time.