Natan

Sznaider

The Venture of the Public Realm: Hannah Arendt meets Günter Gaus

Read the original German version of this article here.

Issue #02 — Transforming Environments

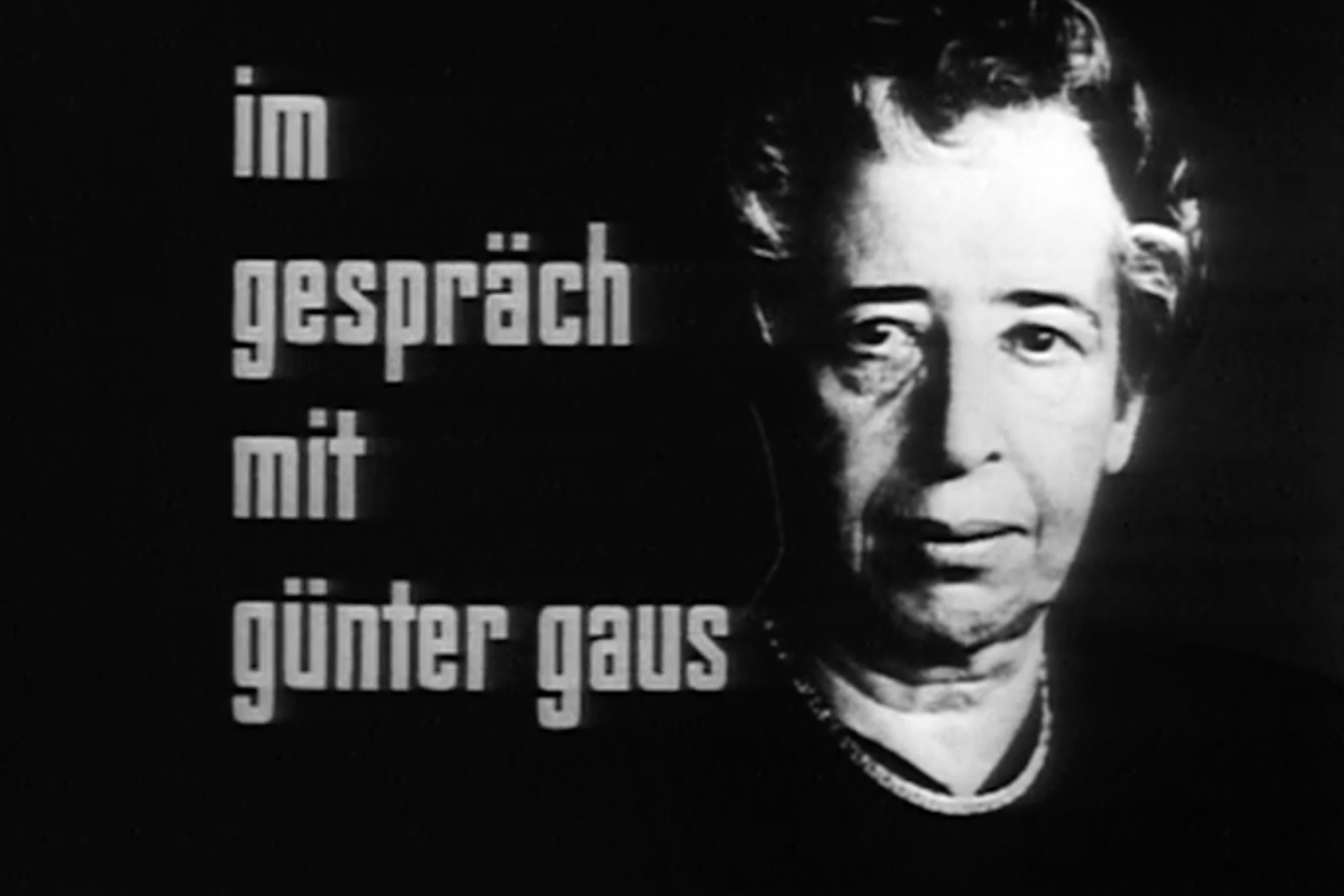

It is the 16th of September 1964 in the studio of the new ZDF, the Second German Broadcasting Company. The stage was set for a man and a woman to record an interview, which was to be broadcast only once.

If you watch the interview today, you will see that the man looks quite tense. It’s not easy for him. His interviewee was already a famous thinker, an older woman, a Jewish woman who had found a new home in New York. He, 23 years her junior, is one of Germany’s most respected journalists, at the beginning of a great journalistic and political career. The curtain rises and the show begins.

In the prologue the Jewish woman claims that she is not a philosopher. Our journalist plays the confused one, insisting that she is. Viewers might think that this is not a good way to start a conversation. The woman explains herself and tries to enlighten our journalist about what she thinks it means to be a thinking person in the world. She emphasizes that politics is about acting in the world, while philosophy is about thinking about the world. This may be difficult for him to understand, but the tension between thinking and acting determines the woman’s existence. This is the basic tenor of her life. That is what this conversation is about.

A few weeks later, on October 26, 1964, at 9:30 p.m., the newly established ZDF broadcast the interview. There was no mention of it in the newspapers.

Arendt rarely talked about herself. Here she makes an exception.

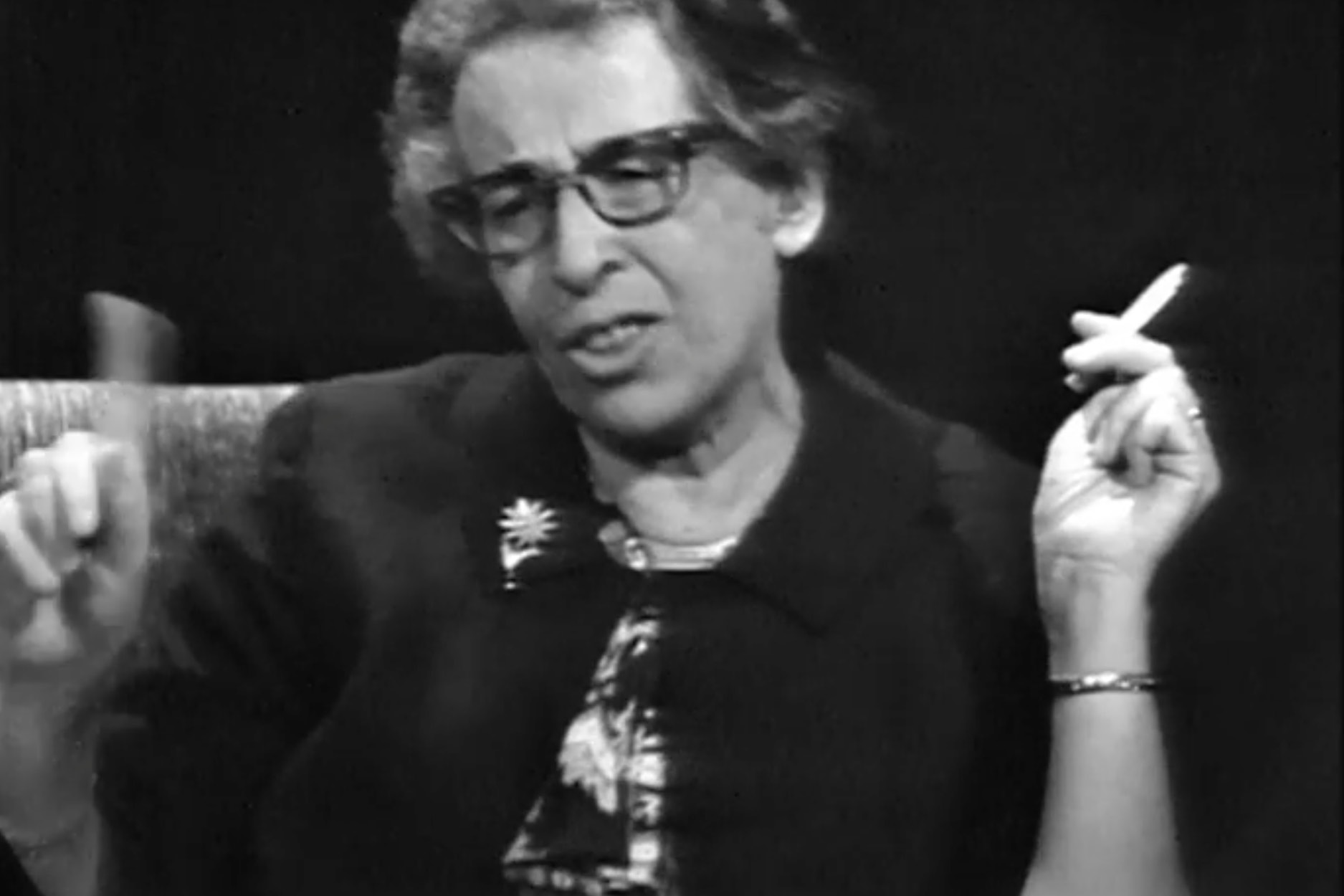

“Zur Person” is the name of the later legendary program, the first version of which was broadcast between April ‘63 and April ‘66. Hannah Arendt was the 17th guest, the first woman after 16 men, in a series of interviews conducted by Günter Gaus, who later went into politics. Both are smoking during the show, so we know it is an older program. The two talk about philosophy, writing, the role of women, Arendt’s Jewish childhood, emigration, the Holocaust, and her infamous Eichmann book, which had just been translated into German. This German translation was actually the reason why she was in Germany and why Gaus interviewed her.

Arendt rarely talked about herself. Here she makes an exception. She is visibly nervous, but her nervousness only makes her more focused in her language and in her answers. She speaks very clearly, her German sharper than ever. Like everyone else, Hannah Arendt carries her personal, family and collective history with her. Every single sentence bears witness to this. Born Jewish in 1906, she was only 27 when the Nazis seized power. She fled from the Nazis to France and from there, via Lisbon, to the United States in 1941. She lived through the war and the so-called post-war period in New York. But there is no post-war period for Jews. The time after the Shoah is never ‘after’, it is always in the here and now.

Arendt knows that she is already famous at the time of the interview. Her books have been published, the book on totalitarianism, the book on Rahel Varnhagen, the book on the Eichmann trial. In 1959 she was awarded the Lessing Prize of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg. She wanted to be seen and heard. Jews had not been heard in Germany for a long time. At first, she was flattered by the attention. As a Jew, it was not a matter of course to be invited. Arendt and Gauss are gifted actors, they both play their roles. It is not a monologue, but a dialogue between generations. Gaus, born in 1929, embodies the new Germany after the Nazi era. He was a left-liberal journalist, part of the new West German elite. He believed that, as a German, he could speak freely with a Jewish woman.

But this is about more than the German-Jewish conversation. Arendt is the first woman to take part in this ZDF discussion series. We are witness to an unusual conversation between a man and a woman. Arendt speaks openly about the role of women, which she hadn’t done very often, perhaps it was the first time she had done it in public. She was not exactly known as a feminist. She sneers at the male desire for importance. But behind the dialogue between generations and genders, there is another layer that is more difficult to recognize; it is a dialogue between a German man and a Jewish woman. The language may be deceptive; both speak brilliant German. Arendt was educated in Germany, and it shows. At first glance she could be mistaken for a German woman.

»

It wasn’t the German language that went mad. And secondly, there is no substitute for the mother tongue.

«

As simply as she says these words, she was aware that it had always been confusing that Jews spoke and wrote German and yet were not Germans. After 1945 this is even more ruthless than before, because it creates the illusion of a conversation and at the same time controls its boundaries. The language does not betray it, but this is not a dialogue between two Germans, but a dialogue between a German and a Jewish woman, and more than that, an American Jewish woman, which Arendt already was at the time of the interview. Arendt had been living in New York for more than 20 years and Gaus is well aware of this. After talking briefly with her about politics and philosophy and what it means to write, he asks her why she had to leave Germany in 1933 after her brief arrest for being Jewish. This is the crucial point in the conversation. Exile became a state of mind for her. The anti-Jewish world became the focus of her thoughts and actions. She was granted American citizenship in 1951, which not only changed her legal status but also gave her existential security as an American.

The interview grows in intensity. As a thoroughly Jewish thinker, she emphasizes, after a short detour into her childhood, the catastrophe of the Shoah, the rupture of civilization for Jews and the world. She has always been concerned with Jewish visibility, and the politicization of this visibility is also the state of Israel. As she clearly states:

»

If you are attacked as a Jew, you have to defend yourself as a Jew. Not as a German or as a citizen of the world or of human rights or anything else.

«

And then, of course, Adolf Eichmann, about whom she wrote in her trial report. Here at Gaus, she repeats her basic thesis:

»

But I was really of the opinion that Eichmann was a buffoon.

«

What she insinuates is that his sentences sound as if they have been memorized. He answers questions with memorized phrases, and it’s as if these clichés allow him to concentrate and trust himself. She saw him almost as an empty shell, without an inner life, without a conscience, filled with platitudes that he calls up at the right moment. Just a buffoon spouting banalities. And so Arendt unfolds the concept of the banality of evil with an almost poetic tone.

And as a Jewish woman who was born in Germany, studied there, and lived there until her mid-twenties, she constantly asked herself how she, as a Jewish woman, could speak to Germans and in Germany in German. This is the only way to understand and comprehend her conversation with Gaus. How can the inner Jewish language be linguistically translated to the outside world? What language is appropriate to describe, even explain, what happened from a Jewish perspective in German to a German audience when one is still speechless? So how to have an honest conversation? We don’t really know, but Arendt does appear on the ZDF stage. She dares to go public with this conversation, just as all Jews in Germany must dare to go public.

She concludes the interview by saying the following emphatic words:

»

The risk of publicity seems clear to me. You expose yourself to the public, as a person. Although I believe that one should not appear and act in public and reflect on oneself, I know that in every action the person is expressed in a way that no other activity can. Speaking is also a form of action. So that is one thing. The second venture is: we start something; we weave our thread into a web of relationships. We never know what will become of it. We are all dependent on saying: Lord, forgive them for what they do, for they know not what they do. This applies to all actions. Simply because you cannot know. That is a risk. And I would say that this risk is only possible by trusting people. That is, a – difficult to grasp exactly, but fundamental – trust in the humanity of all people. Of all human beings. There is no other way. The venture into the public realm seems clear to me. One exposes oneself in the light of publicity as a person. If I am of the opinion that one must not appear and act self-consciously in public, then I also know that in every action the person is expressed in a way that is unlike anything else the person does. Whereby speaking is also a form of action. This is one venture. The second is: we start something, we weave our thread into a network of relationships. We never know what will come out of it. It is imperative to say, “Lord, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” This is the case for all action. Simply, quite concretely, because it is not possible to know it. It is a venture. And I would say that this venture is only possible through trust in other people—through a difficult to grasp but fundamental trust in the humanity of all people. Without this it is impossible.

«

After this sentence, Hannah Arendt looks into the camera, somewhat distraught. Since 2013, more than a million people have watched the interview on YouTube, a platform that neither Arendt nor the journalist Günter Gaus knew about in their lifetimes. A public undertaking indeed.

Translation: Dr. Daniela Schröder

Natan Sznaider

is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at The Academic College of Tel Aviv-Yaffo. Sznaider has also taught and conducted research at Columbia University, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and Ludwig Maximilian Universität in Munich.

The central themes and questions of his research are cosmopolitanism, memory, anti-Semitism, sociology of knowledge, Hannah Arendt, political theory, and the Shoah.

The interview is published in: Hannah Arendt, Ich will verstehen. Selbstauskünfte zu Leben und Werk, München, 2005, S. 46-72.

Image information: All images are taken from the ZDF documentary Hannah Arendt – die politische Denkerin – ZDFmediathek