What is Water?

A River Walk by

Tobias Schmitt &

Katrin Singer

Issue #02 — Transforming Environments

Water is everywhere. It flows through our city, our homes, our bodies. It rains, seeps away, evaporates and yet always reappears. It condenses into a river and thus shapes the image of the city of Hamburg.

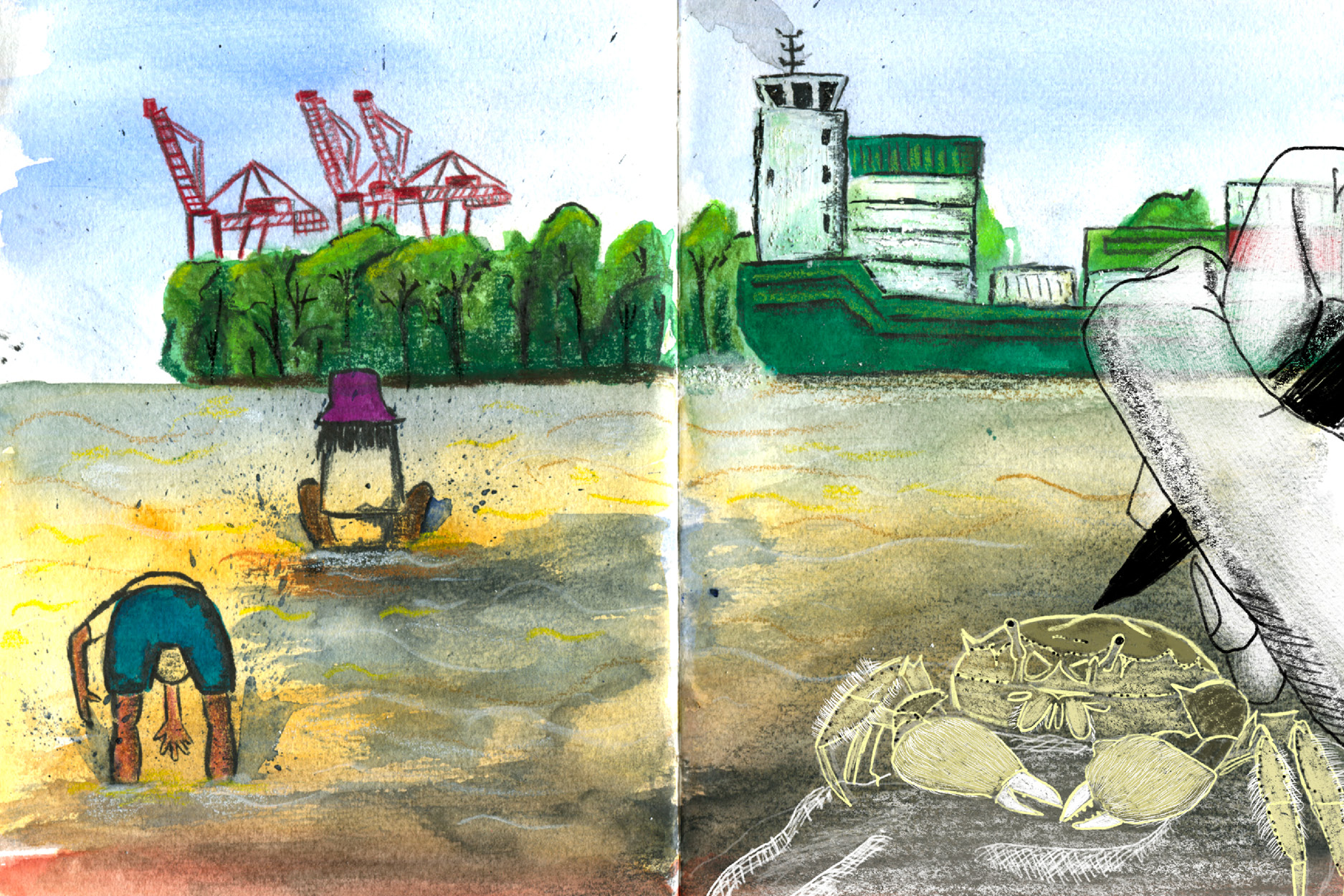

Hamburg, its port, its Hanseatic and colonial history, and its tourist attractions are all inextricably linked to the Elbe. We (mostly) take water for granted, yet it is a vital commodity. Water is life and brings death. Water can take on all aggregate states and forms, yet it slips through our fingers when we attempt to grasp it. Like water, the various representations and narratives of water are fluid and fluidic.

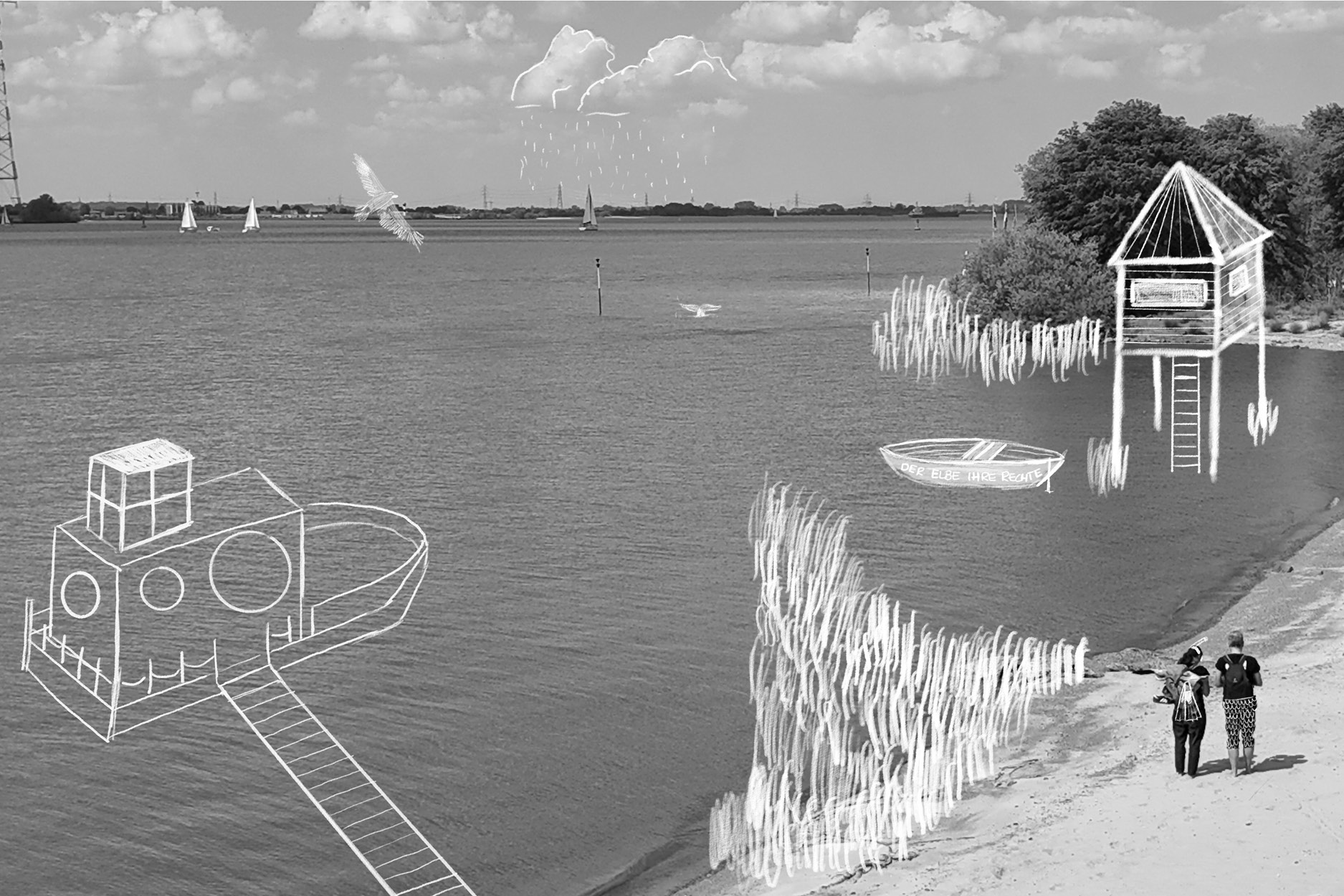

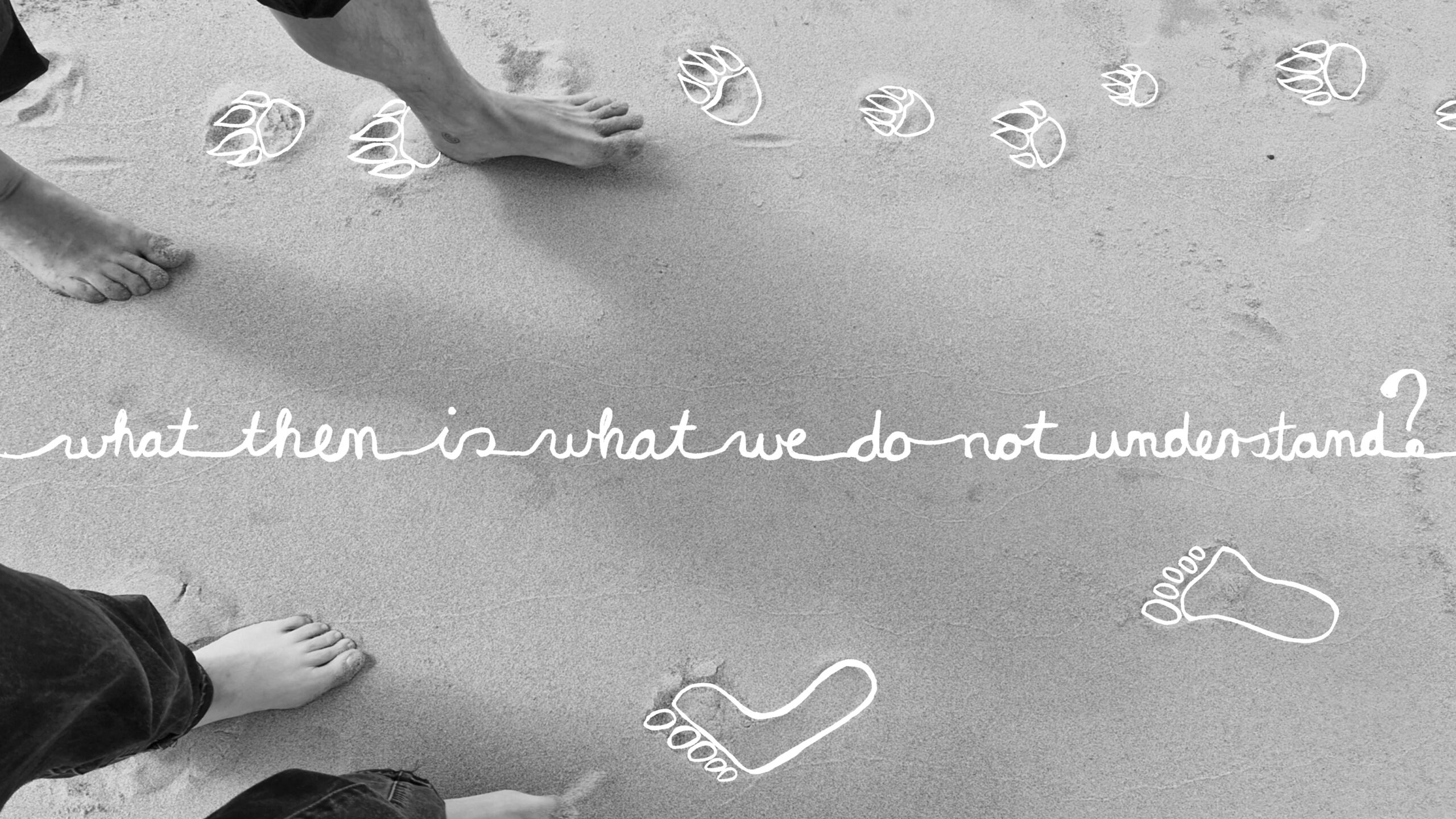

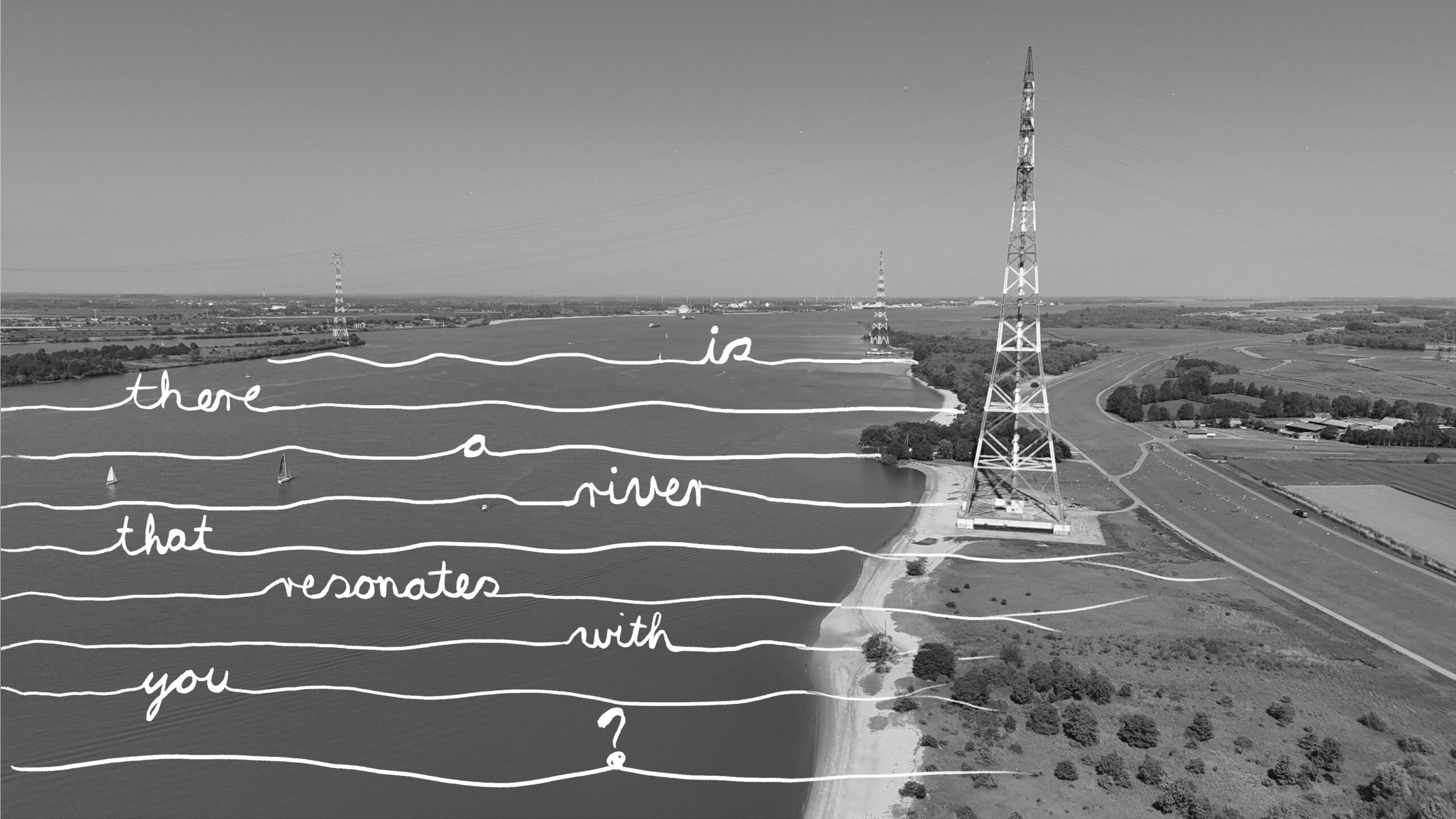

What, then, is this substance that we call water? To answer these questions, we embarked on a journey to the River Elbe, the lifeline of the city of Hamburg. During this expedition, we engaged in a theoretical and artistic-creative exploration of the river, the water and ourselves. The theoretical and conceptual considerations (Schmitt 2022) led to the development of a river walk by Tobias Schmitt (conducted in German), which we used to move along the Elbe, discussing, photographing and painting along the way. Therefore, this article is a translation of the audio walk and an invitation to readers to set out and follow the water themselves. We invite you to open up to the ideas that flow, and to ask yourself what a more amphibious life might look like…

The Water Cycle —

«What do we know?»

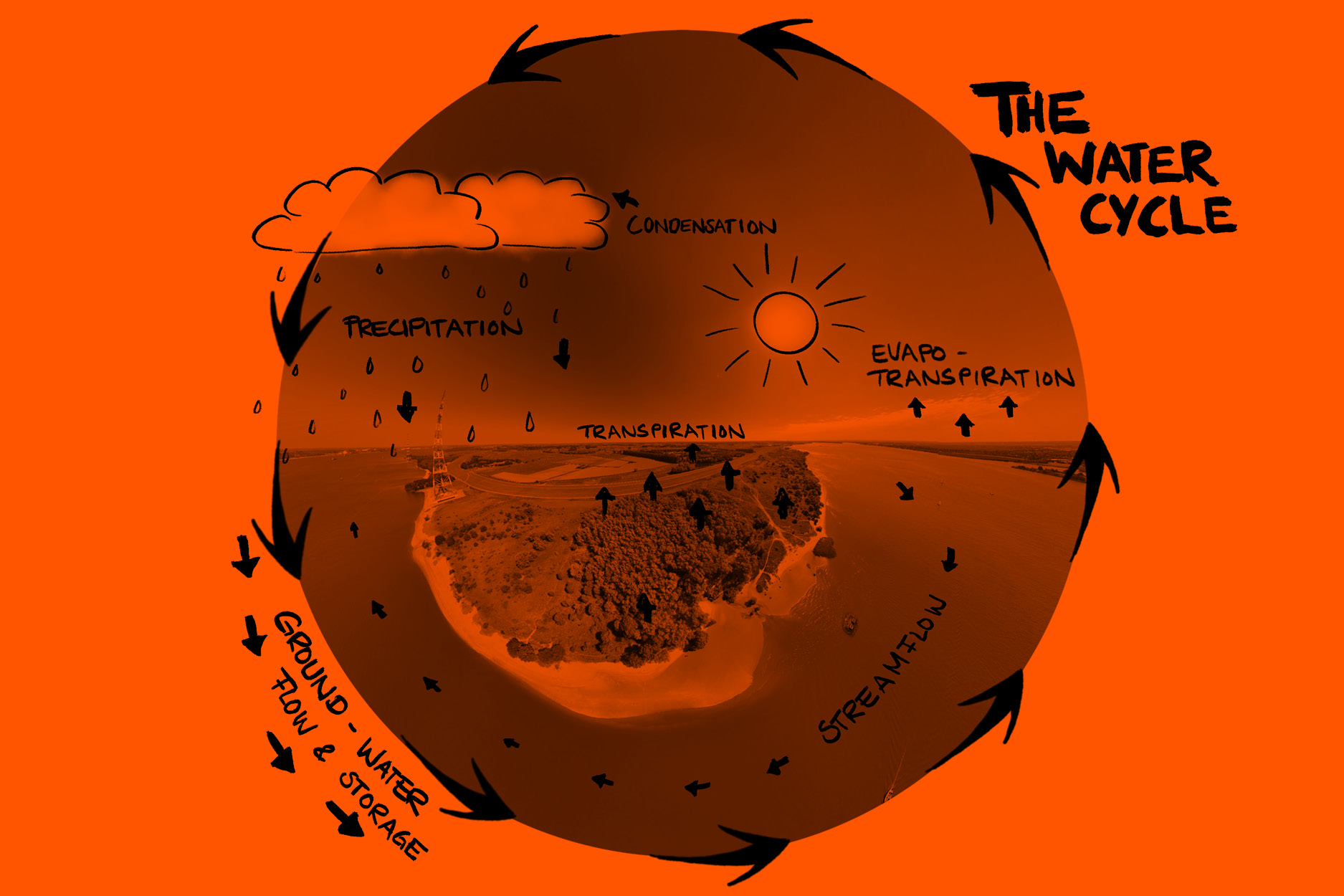

The question of the origin and destination of water has been the subject of considerable debate. What images do you associate with the concept of the water cycle? It is fair to say that most people will immediately think of a diagram with a sea, mountains, rivers, lakes and arrows, illustrating the eternal water cycle. Do you see human beings within your conceptual framework? What is the objection to this representation?

It is not intended to negate the hydrological cycle or declare it false, but to distinguish between representation and reality. The water cycle remains one of the most powerful representations of ‘modern water’, as Jamie Linton (2010) has termed it. However, it is crucial to recognize that the water cycle is not a neutral scientific concept. Rather, it is a social construct with political implications that has emerged in a specific historical and social context. It is based on a particular understanding of nature, is linked to particular interests and uses a particular form of expertise.

This has led to the creation of a scientific discipline centred on the water cycle, which has privileged a specific, predominantly engineering-related body of knowledge, legitimized certain forms of water use and promoted the institutionalization of water governance and management. We have learned to understand water through certain scientific discourses and representations, which have led to the perception of water as timeless and ahistorical, as well as natural and untouched by social conditions. In his book “H20 and the Waters of Forgetfulness”, the theologian and philosopher Ivan Illich describes how modern society has developed the idea of water as a scientific abstraction, thereby demystifying this substance called water. This process effectively erased the water’s historical context, making it difficult to comprehend water’s “deep imagination” (Illich 1985: 75). The abstraction of concrete social contexts also made it possible to understand water as a resource at all. Furthermore, the progressive commodification, valorization and privatization of water within a capitalist mode of production is also based on the concept of water as an entity that can be separated and delimited from nature, which can be measured, owned, valued and sold (Köhler 2008: 20).

Being Water —

«What do we taste and feel, and what are we?»

Since our bodies mainly consist of water, we cannot treat water as an independent, sovereign subject. The concept of the “irrevocable dependence of man on water” challenges the traditional dichotomy between man and water and between man and nature. It suggests an existential, intimate, and embodied relationship between these entities that is no longer clearly defined as internal and external. As Alfred North Whitehead observed: “We are in the world and the world is in us” (Whitehead 1934 as cited in Linton 2010: 224). Water has always been both a material and an ideal component of thinking, naming and imagining. Water is involved in all the physical processes (such as the provision of nutrients and oxygen, digestion or the regulation of body temperature) and mental processes (such as the transmission of neurotransmitters) of human existence. It also provides the imagination for thinking in movement and fluidity.

Understanding the human body as a “body of water” (Neimanis 2013) also means understanding how we are embedded in a (natural) world in a very material way. The water that we absorb and excrete, that flows through us and keeps us alive, connects us beyond the boundaries of our bodies to other human, animal, plant, geophysical and meteorological bodies of water. The presence of water serves to blur the boundaries that are typically perceived as stable and absolute, and to facilitate the mediation between different scalar and temporal levels. Water plays a pivotal role in both cellular osmosis and planetary circulation. It connects freshly fallen rainwater with centuries-old groundwater reservoirs and can constantly switch back and forth between different aggregate states. Water thus acts as a mediator between entities, “because water knows no borders; because it not only moves in a complex natural world cycle, but also flows through the bodies of all people and living beings at every moment, as well as the bodies of societies, houses and factories, cities and villages, and because this anthropogenic cycle is inevitably included in the natural cycle of water and changes it at the same time” (Böhme 1988: 9).

Water as a social relationship to nature —

«What do we understand?»

Understanding the mutual influence of water and society can be taken even further. Rather than assuming a pre-existing relationship between water and society, where the two entities exist independently of each other and only engage with each other as such, we propose that water and societies emerge from reciprocal relationships: the constitution of societies depends on their relationships with water. Rather than simply flowing through streets, factories, homes and bodies, water plays a constitutive role in organizing and structuring social relations, imaginations and cultures. The seasonal rhythm of precipitation regimes and rivers can determine the rhythm of economic activities, eating habits, transport options and accessibility, festivals, and anniversaries. This, in turn, creates identities and social formations.

Conversely, the specific conception of water, its material and discursive constitution, emerges from social relations. Consequently, water and its particular physical and chemical properties can only be produced with specific knowledge, technologies, cultural, spiritual, economic and political arrangements, and concern for the unique needs of the human body. Water manifests in a variety of ways: as H2O, as one of the four elements, as drinking water, as a source of life, as a river, as a snake, as a limited entity, as a holistic system, as a flood, as God’s punishment, and so on (Schmitt 2017).

This co-constitution of hydro-social relations (Linton & Budds 2014) is always contingent on historical and socio-material conditions. The characteristics of water arrangements vary according to the geographical context. For instance, the water arrangements in desert regions differ from those in tropical rainforests, while those in island regions differ from those in mountainous regions. Similarly, water arrangements in agrarian, spiritual societies differ from those in urban, modern and secularised societies. However, such a co-constitution implies that water can only be integrated into the hydro-social relations through the prevailing material conditions. The fundamental properties of water are its ability to follow the force of gravity, its capacity to dissolve substances, its tendency to change its aggregate state in response to temperature, its tendency to mix and change its quality, its specific surface tension, its density anomaly and its conductivity. The materiality of water thus allows it to enter into relationships with human and non-human actors and to constitute connections.

Indigenous Waters

At a meeting of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous communities protesting against the diversion of the São Francisco River in north-eastern Brazil, Marcos Sabaru, representing the Tingui-Botó Indigenous community, gave a speech from which the following extract is taken:

“Talking about the Rio São Francisco is an honour for me because I am talking about my home. Because from our point of view, the Indigenous point of view, there is no river, no human being, no animal, and there are no plants. It is all one entity. For us (…) the river is a sacred place, a dwelling place for us humans, a source of life, a source of food. So sometimes it bothers me when people talk about the river and use words like water resources. I think we should not talk about the river as if it were just water. We should talk about the river as a people. We should talk about the river as a bank, a human being, a fish (…) We should understand that it’s all one and not just talk about water, water, water and forget about the people, the living beings, the shore, the faith” (Sabaru 2008: own recording).

Understanding water as a unifying element that transcends the boundaries between human bodies, rivers, fish, trees and clouds, between the material and the social dimension, may seem challenging to those who espouse ‘enlightened’, ‘modern’ thinking. In many Indigenous ontologies, however, relationships and mutual responsibility are deeply embedded. Two feminist Indigenous scholars, Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy, have described this way of thinking as ‘radical relationality’. This concept holds that the self can only be thought of and experienced as part of the other, and that the other always exists as part of the self. In this context, Yazzie and Risling Baldy conceptualize the relationship with water as a form of kinship based on responsibility, reciprocity, and respect:

“We conceive of radical relationality as a term that brings together the multiple strands of materiality, kinship, corporeality, affect, land/body connection, and multidimensional connectivity coming primarily from Indigenous feminists” (ebd. 2018: 2).

Water is a kind of teacher or guide that leads and unites the struggles for decolonization. For example, the slogan «Mni Wiconi — Water is Life» was central to the resistance against the Dakota Access Pipeline in the United States.

Water is a kind of teacher or guide that leads and unites the struggles for decolonization. For example, the slogan “Mni Wiconi – Water is Life” was central to the resistance against the Dakota Access Pipeline in the United States. It unified several hundred Indigenous groups and allowed them to unite their different struggles, origins, and orientations. In Aotearoa (New Zealand), the Whanganui River was legally recognized as a distinct entity in 2017, following a 140-year struggle by the Māori to have their relationship with the river recognized (Wilson & Inkster 2018). Recognizing rivers as subjects with inherent values, rights, and voices, a notion advocated in countries like India, Ecuador, and Colombia, demonstrates a deep respect for Indigenous ontologies and their principles of reciprocity, responsibility, and respect. This actively challenges the Western anthropocentric perspective focused on (property) thinking.

At the same time, Indigenous scholars such as Sarah Hunt have highlighted the potential dangers and pitfalls of uncritically adopting and appropriating Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies. If Indigenous concepts are used merely as a source of inspiration, without acknowledging the complex knowledge systems, lived practices and experiences of Indigenous peoples embedded within them, and without challenging the dominance of Western structures and knowledge systems, then the reference to Indigenous ontologies ultimately constitutes a form of ‘epistemic violence’ (Hunt 2014).

In her book “Confluencing Worlds”, Katrin Singer also highlights the potential dangers of exoticizing and appropriating Indigenous (water) ontologies from a Western perspective. She combines her analysis with reflections on her own positionality, the dangers of complicity with the coloniality of knowledge, and questions about the (im)possibility of unlearning dominant Western ways of thinking and interpreting (Singer 2019).

Concluding Remarks —

What can we learn from this?

The water debate is not just an object of social discourse. Instead, it can be used to illuminate the interconnections between social relations and the natural world, thereby facilitating a deeper understanding of the relationality of social relations to nature. For instance, Jessica Hallenbeck notes that “centering water opens up space for political and relational attention toward the bodies, beings, stories, and histories that run through it” (Hallenbeck 2015 as cited in Stevenson 2018: 103). Recognizing the existential importance of water for all life and the regenerative power of water also implies that the concept of an agency of water is no longer a mere epistemological consideration, but rather a significant aspect of water relations. The concept of water challenges the traditional understanding of clearly definable, fixed, separate and constant entities and opnes up new possibilities for fluidity, circulation, the indeterminate and the boundless. The concept of “thinking relationships through water”, as articulated by Franz Krause and Veronica Strang (2016), can help to overcome dichotomous thinking and facilitate the identification of connections that might otherwise remain obscured.

Listen the

Audio Walk along

the river here:

Translating proofreading: Dr. Daniela Schröder

Katrin Singer

is a postdoc at the University of Hamburg. Her geographical work is inspired by theoretical thinking from the fields of critical geography and feminist political ecology. Along a spectrum of cartographic, artistic and methods, she follows ethnographic traces and river-based research in Europe and South America.

Tobias Schmitt

is a geographer and part of the working group »Critical Geographies of Global Inequalities« at the Institute of Geography at Universität Hamburg. His focus is on political ecology and post- and decolonial theories, whereby reflections on water permeate many of his works.

Image Information

Photos: Tobias Schmitt and Katrin Singer

Illustrations: Katrin Singer