Reinaldo

Funes Monzote

Environmental

History and Climate

Change in the

Caribbean

Issue #02 — Transforming Environments

Environmental history is a field that transcends disciplinary boundaries, connecting researchers from the humanities and social sciences, as well as the natural or basic sciences. It is a rich and diverse field of historical studies with more than half a century of formal existence.

Fifty years ago, the American Society for Environmental History was founded as the first association to promote this interdisciplinary approach in the United States. After some efforts since the late 1980s, the European Society (ESEH) was established in 1999, and others like the Latin American and Caribbean (SOLCHA) were organized in the following years. Finally, in 2009, the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations (ICEHO) joined the stage, further highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of this field.

Since the 1990s, environmental issues have gained increasing prominence in Latin America and the Caribbean’s social movements and governmental agendas. With their multidisciplinary approach, the scholars have played a crucial role in this process. Environmental historians have contributed significantly to the debates around the so-called Anthropocene or Capitalocene, inspiring political ecology and ecological economy discussions. The evolution of the environmental question will remain central, whether in a present world order or a new one.

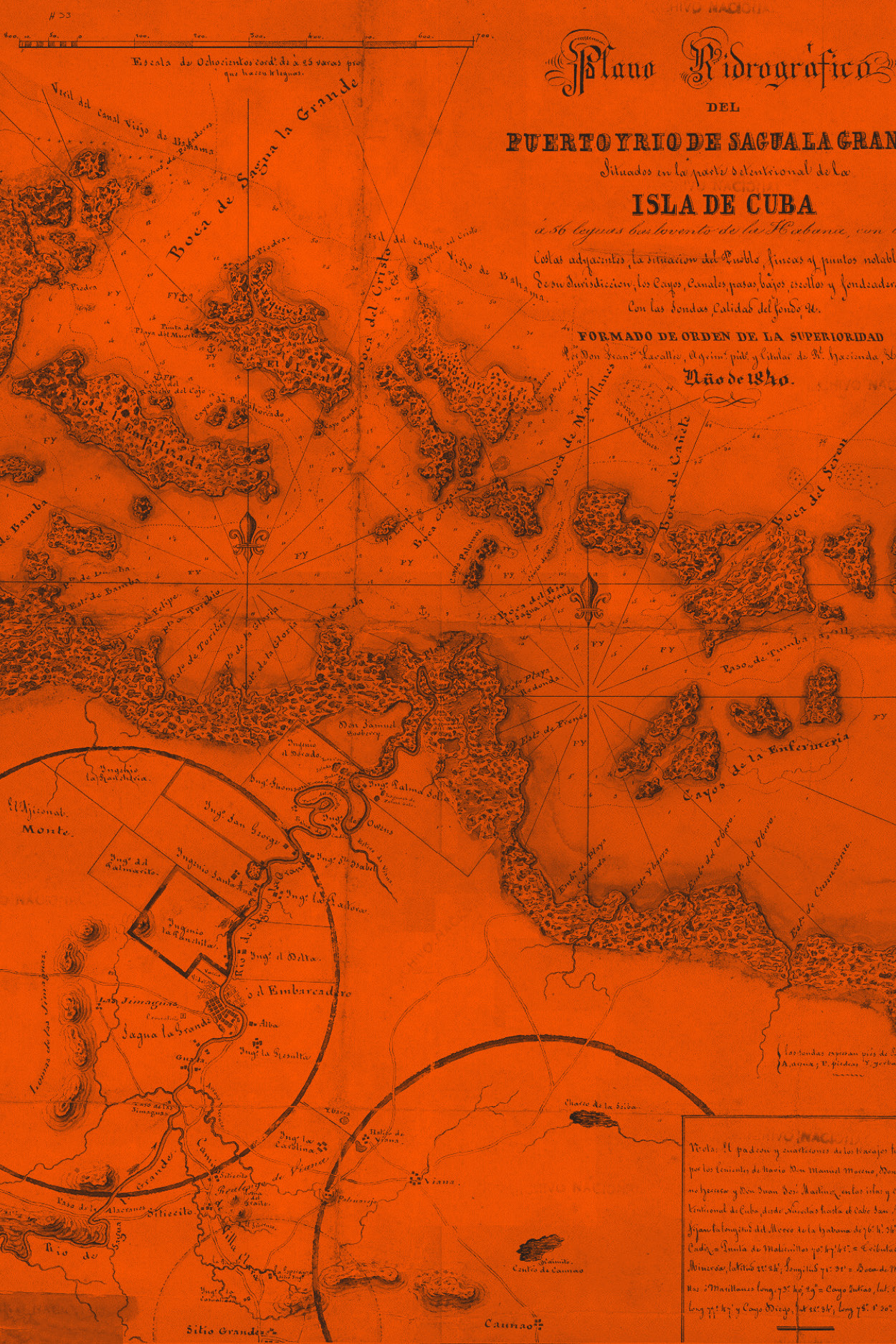

The Caribbean region, both the islands and the surrounding Caribbean Sea basin, was a significant player in the 1492 clash between the Old and New Worlds. It was among the first areas to be part of the post-Columbian globalization process, with the Atlantic world as the center of new European powers established through the possession of colonies on the American continent.

The Caribbean region, both the islands and the surrounding Caribbean Sea basin, was a significant player in the 1492 clash between the Old and New Worlds.

Most of the continental Caribbean, part of the Spanish empire, gained independence after the 1820s. The Dominican Republic broke away from Spain during the Haitian occupation of the entire island in 1822 and later, in 1844, became an independent republic. In 1898, the Spanish colonial presence in Cuba and Puerto Rico ended, marking the beginning of the United States’ dominance over the entire Caribbean basin. This included the a growing influence over independent republics or the colonies of England, France, and Denmark. However, the United States’ hegemony was not unchallenged. The Caribbean’s spirit of resilience was evident in the region’s resistance and challenges to this dominance, particularly after the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

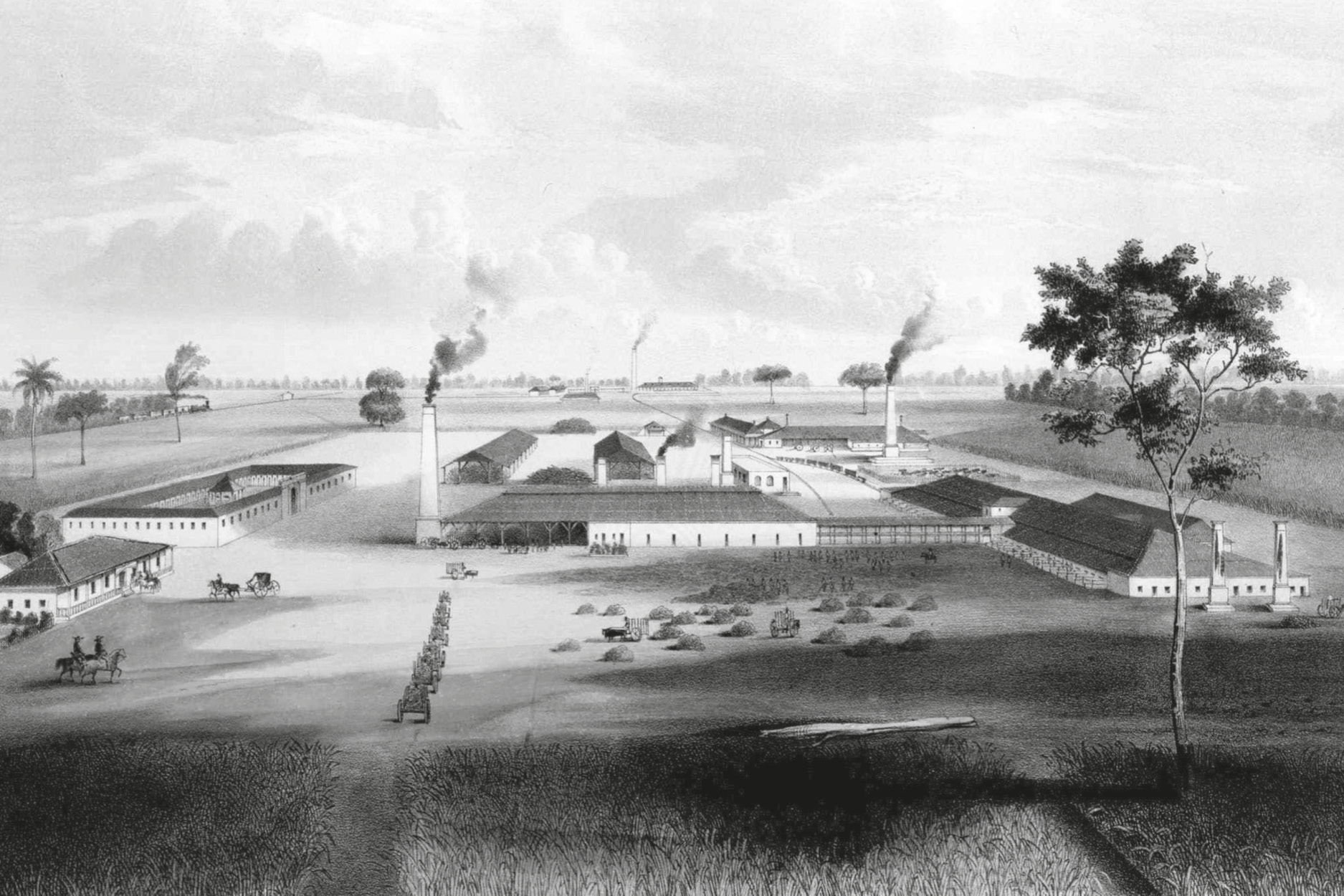

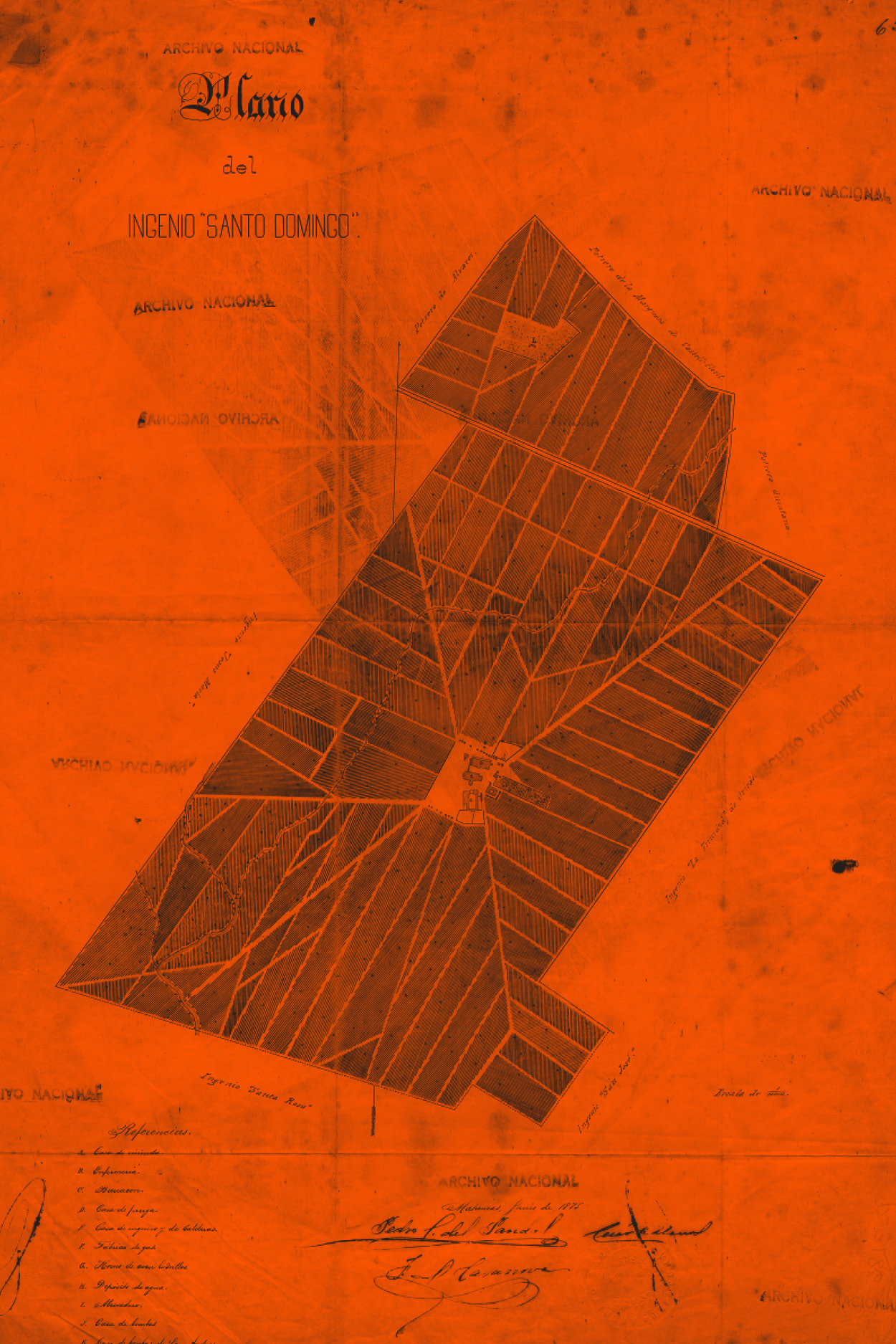

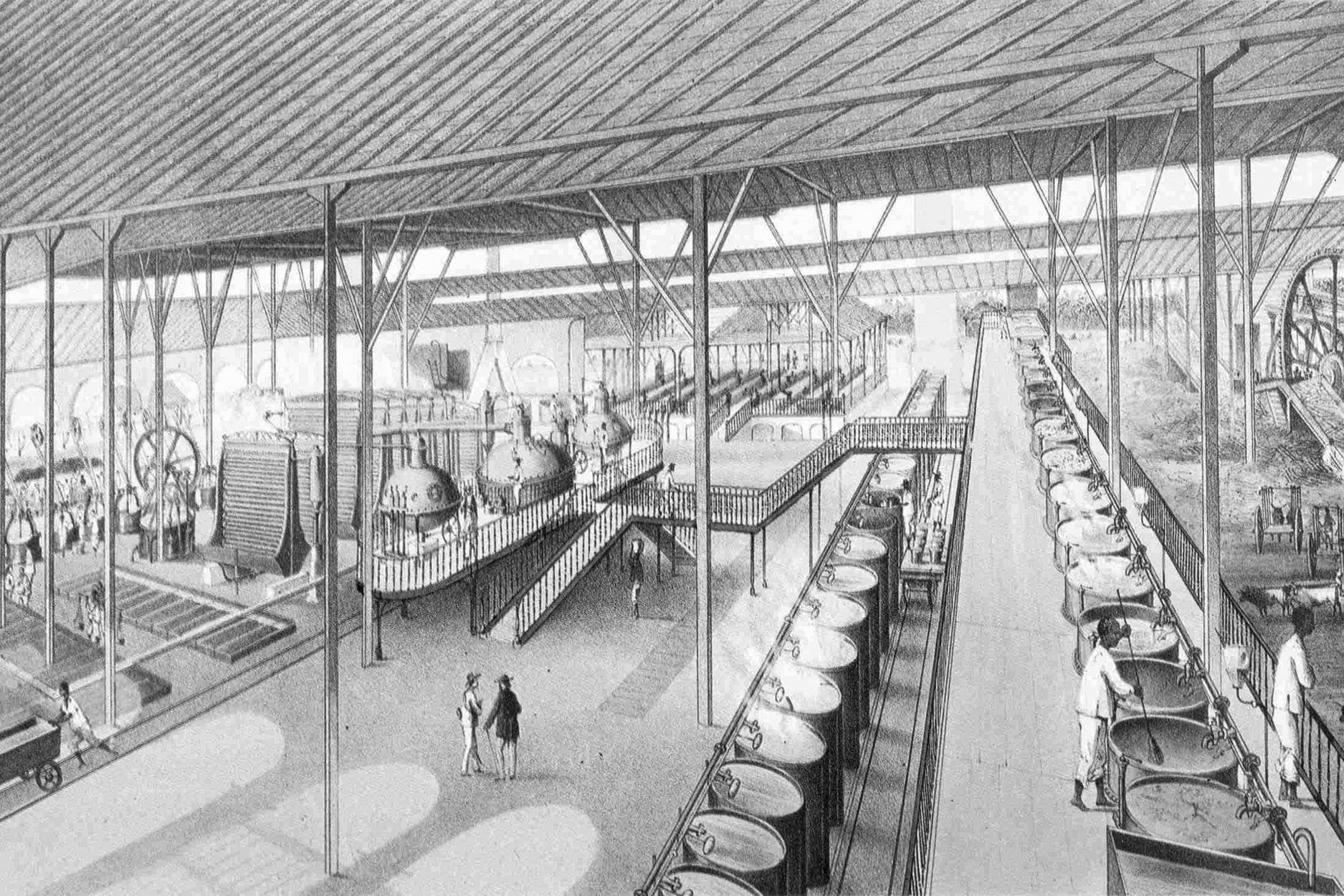

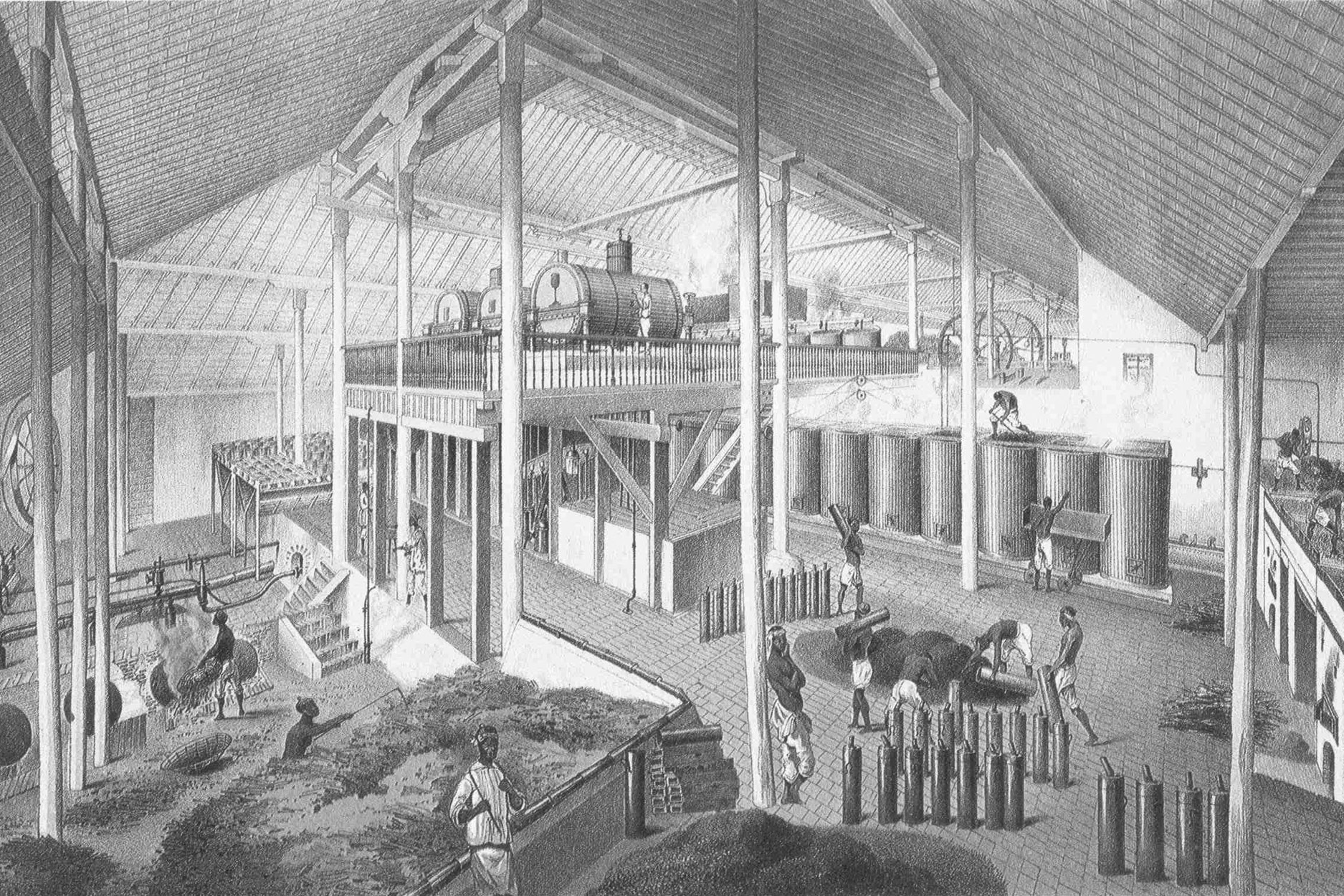

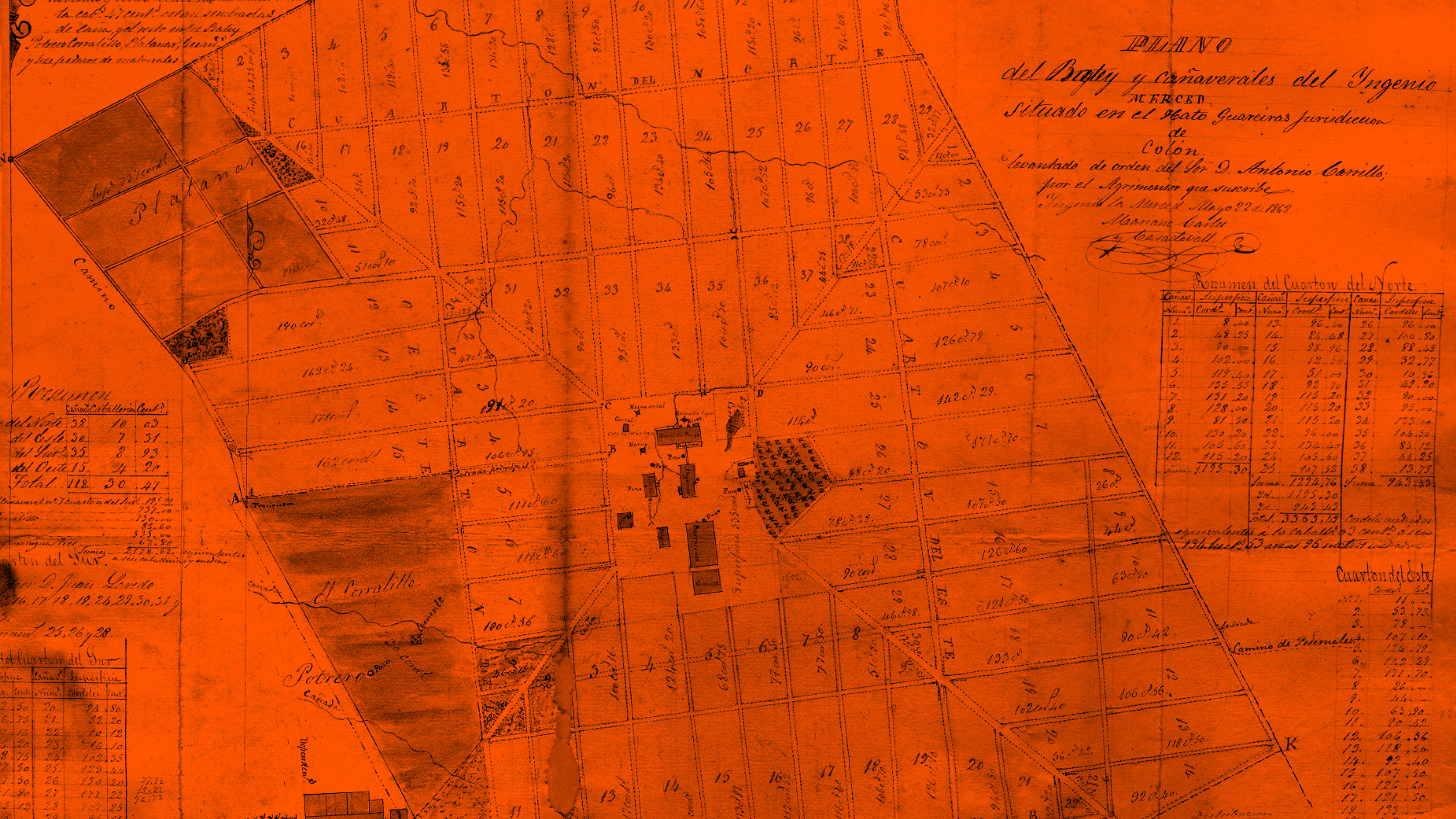

A common characteristic of the hegemonic powers in the Caribbean is that all the metropolises were part of what has been known as Western civilization. Colonial control over the Antilles and other territories around the Caribbean Sea contributed to the idea of the superiority of the West over Asia and Africa. The so-called sugar revolution from the mid-17th century and the formation of the slave plantation system in the non-Spanish Antilles were a central ingredient in the growing differentiation between Europe and other regions of the world. That gap widened with the Industrial Revolution and a new socio-metabolic regime that spread from Great Britain to different areas of Europe and the United States.

In his opinion, the »sugar and slave islands« had been transformed into European workshops, specialized in a few colonial crops, where the order of nature had been reversed.

At the beginning of the transition to an industrial age, after a visit to the Americas between 1799 and 1804, Alexander von Humboldt criticized the colonial system created by Europeans, especially the French and British in the Caribbean. In his opinion, the »sugar and slave islands« had been transformed into European workshops, specialized in a few colonial crops, where the order of nature had been reversed. This also included the denunciation of the massive employment of enslaved Africans as a labor force. In some way, the Caribbean colonial plantations represented an antithesis of the European enlightenment.

The tropical climate was one of the arguments used to justify enslavement and later racialized labor, arguing that white Europeans were less able to withstand the heat and humidity. The material and intellectual differentiation through colonialism and imperialism between temperate and tropical climates is at the origin of dichotomous terms that express the inequality of the current global system: Core and Periphery, First and Third World, Development and Underdevelopment, and North and South.

Two centuries after Humboldt’s ideas about the plantation system and slavery, much has changed in the region because of the global rise of industrial society and its ramifications. However, the form of insertion into the world order that emerged with the European colonization of America remained similar. Paraphrasing Humboldt, one could say that the order of nature continues to be inverted for the region’s countries. It is no longer the classic plantation to produce sugar, coffee, or bananas, although those crops are still present in some territories. It has now been transformed into a mass tourism destination, mainly from the old colonial or hegemonic powers. As one of the favorite spots to enjoy tropical nature and be served by its inhabitants, the Caribbean is today considered part of the “periphery of pleasure.”

In the new era of uncertainty about the emergence of a new global order, the Caribbean countries are seeing new paths that allow a greater margin of independence and equidistance from the former colonial powers.

This shift from plantations to mass tourism is the best example of the socio-ecological transition on our planet to a society dominated by industrial metabolism over the last two centuries. From organically based agrarian or agro-industrial societies dedicated to the export of calories to the world market to a leisure destination for the masses of workers from the industrial North, most of them. Therefore, instead of exporting calories, a high amount of energy and materials must be imported to sustain a service economy that resembles the colonial relation of the old plantation model.

In the new era of uncertainty about the emergence of a new global order, the Caribbean countries are seeing new paths that allow a greater margin of independence and equidistance from the former colonial powers. The main challenge is to be able to speak with one voice in the face of the old idea that because they are small countries or because of their heterogeneous populations, the possibilities for effective self-government would be limited. The people and governments of the region assume a proactive position and create their organizations or new alliances. In some cases, this attitude takes the form of a demand for reparation for the damage caused by the massive use of slave labor in the past. One might ask whether this demand could include the ecological debt generated by plundering the region’s ecosystems or unequal economic exchange.

The Caribbean, especially the islands, are among the most vulnerable in the region to climate change threats.

The Caribbean, especially the islands, are among the most vulnerable in the region to climate change threats. Most of the archipelago’s nations are part of the Small Island Development States, a category created by the United Nations in 1994, even Cuba, which is the largest. The threats of natural hazards like hurricanes, volcanoes, earthquakes, floods, landslides, or droughts are many new threats associated with global warming. These include rising sea levels, intensification of water scarcity, growing incidence of tropical diseases, increasing fragility of coastal zones and coral reef ecosystems, and impacts on agricultural activities.

Of course, countries in the region confront environmental or social challenges differently depending on their geographic characteristics or historical processes. In general, however, we can find many similarities that contribute to more robust connections to collectively face the new world order in the age of climate change. A deeper understanding of the region’s common environmental history and the specificities of each place would contribute to the goal of a new, more just, and equitable global order that considers the interests of small nations.

Incorporating the environmental turn in the study and reconstruction of the Caribbean past will help to raise awareness to confront the challenges of climate change, the depletion of natural resources, the loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, pollution, and the scarcity of drinking water. As one of the most vulnerable regions in the world to all these threats, the region is looking for more sustainable development, such as the so-called “carbon-free vacation” for the tourist sector. Climatic vulnerabilities are linked to historical patterns, but also to new challenges posed by the rise of ultra-nationalism, xenophobia, racism, and climate denialism in former metropolises, which may affect the foundations of the search for effective global solutions to the planetary environmental crisis that threatens the human species and other life forms.

Reinaldo Funes Monzote

Reinaldo Funes Monzote is professor at the University of Havana and coordinator of the Geo Historical Research Program at the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation (Cuba). He is also president of the Cuban Society for the History of Science and Technology and an Academy of the History of Cuba member.

Since the 1990s, he has been involved in the Environmental History movement in Latin America. Collaborations with international research teams have contributed to expanding his research on the relationship between slavery and the socio-ecological consequences of the plantation system, agrarian metabolism, and commodity frontiers. Recently, he aimed to write a synthesis of the Greater Caribbean environmental history.

Image Information

File:Ingenio Acana 1857.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

Eduardo Laplante (lit.), Ingenio Purísima Concepción (a) Echeverría,… | Download Scientific Diagram

Historia del municipio Sagua la Grande (provincia de Villa Clara) – EcuRed

Interior of a sugar factory in Havana (Cuba). 1857. engraving. 19th Madrid, National Library of Fine Arts Author: Eduardo Laplante (1818-C. 1860). Location: Biblioteca Nacional – COLECCION, MADRID, SPAIN.

File:Casa de calderas del ingenio Asunción.tif – Wikimedia Commons